Anti-Judaism, Antisemitism, Anti-Zionism

Anti-Judaism is opposition to a religion;

antisemitism is directed at a people identified as a race; anti-Zionism, instead,

is the struggle against the existence of the State of Israel and/or even just

against its policies.

These are therefore three different concepts, clearly distinct, and each of them

does not necessarily entail the other two. However, in our time they tend to

become blurred, also because, generally speaking, all three end up targeting the

same people: the Jews.

Jews are in fact seen as belonging to a different religion (even if in reality

many do not actively follow it), as a genetically defined people (even though

they are physically diverse), and as supporters of the State of Israel, even

though not all of them are, particularly regarding the policies of recent years.

Let us therefore try to clarify the three concepts.

In the Christian world the distinction was

purely religious. Not only were Jesus and Mary Jewish, but the first founders

and Christian saints were also Jewish. In a world in which religious freedom was

inconceivable, the Jew was at fault for not recognizing Christ and the Good

News, but if he converted he was no longer a Jew, rather a Christian like the

others: by probability, each of us likely has some Jewish ancestor.

For Christians, unconverted Jews were the “deicide people,” those who had

crucified Jesus and had taken responsibility upon themselves and their

descendants (as the Gospels recount). Only with the Second Vatican Council was

it clearly and decisively stated that no collective responsibility of the Jews

exists for that condemnation, and certainly not for the Jews of today.

There was also, and above all, an economic motive: since Jews were excluded from

owning land — the wealth of the Middle Ages — they engaged in commerce, crafts,

and also in lending (usury), which was forbidden to Christians; hence popular

hatred and the desire not to repay debts.

These episodes were always occasional and the Jews waited for them to pass (as

they also did with the Shoah, which instead did not pass).

It was not that Jews were always persecuted, but at times popular uprisings

broke out against them. The reasons were often absurd rumors, such as claims

that Jews supposedly sacrificed children for obscure religious rites. For

example, in Isabella’s Castile the rumor spread that a child who disappeared had

been kidnapped by Jews (el niño de la Guardia, later even canonized), and the

Jews were expelled from the country.

Indeed, while other religious groups — pagans, Muslims in Sicily and Spain,

countless heresies — disappeared, the Jews remained.

Jews are therefore the only ethno-religious

group to have survived from antiquity to the present day: if they had been

systematically persecuted and fought, this would not have happened.

In the Roman Empire, two terrible revolts against Rome led to the massacre of

the Jews of Palestine and to a ban on residing there. Jews who had already

emigrated to the rest of the Empire, however, were not bothered or persecuted (unlike

the Christians). Thus, despite the frightful revolts in Palestine, the Romans

did not view Jews negatively.

Indeed, it is rather strange that although Jews, like Christians, did not

sacrifice to the emperor, they were not persecuted as Christians were. We must

therefore think that the real cause of the Christian persecutions was something

else, not the refusal to sacrifice: the Romans always displayed great religious

tolerance toward all cults.

In the Islamic world as well, there is no record of major persecutions

comparable to those in Christendom, and Jews played a very significant role in

Arab culture and civilization. In fact, Jews were considered, like Christians,

“People of the Book” (Ahl al-Kitab). Only with the founding of Israel were they

expelled en masse from Arab countries (roughly the same number as the

Palestinian refugees).

Antisemitism, on the other hand, is a genetic

prejudice. But the idea that culture is inherited genetically is no longer

accepted by anyone or almost anyone, and therefore this term, now so commonly

used, would no longer make sense.

In the secularized world of the 19th century, religious freedom was established,

including for Jews, who generally became mostly atheists: virtually all those

who contributed to Western culture — from Marx to Einstein to Freud, etc. — were

non-believers.

Thus the shift occurred from anti-Judaism (religious) to antisemitism, that is,

targeting Jews as a lineage rather than as a religion: in anti-Judaism, a Jewish

Christian was no longer a Jew, whereas in antisemitism a Jewish Christian

remains a Jew.

Nationalists began to view Jews with suspicion, considering them

internationalists with relatives scattered throughout the world and therefore

unreliable (the Dreyfus affair, for example).

Then, especially with Nazism, came the idea of race, and thus Jews as a race

improperly called “Semitic” (which actually refers to a group of languages

spoken in the Middle East and would today apply mainly to Arabs).

As for race, aside from obvious somatic differences (the Falasha are even Black),

which show intermixing with other peoples, having a shared genetic heritage does

not imply identical cultural or psychological characteristics.

One might then speak of a national culture which, according to 19th-century

views, characterized each people.

But even this distinct Jewish cultural identity, separate from that of the

peoples among whom they lived, in reality does not exist, apart from religion.

Instead, Jews, no longer distinct by religion, tended to blend into surrounding

populations and thus risked disappearing; the founding of Israel was mainly

intended to prevent such disappearance.

Regarding language, Jews have not spoken

Hebrew since the 5th century BCE, but rather Aramaic (a variant of Syriac or

Assyrian). Later they spoke the languages of the peoples among whom they lived.

Those of Eastern Europe (Ashkenazim) had been expelled from Germany but

preserved the German language of that time (Yiddish): they could understand the

Nazis who deported them.

Those expelled from Spain (Sephardim) often preserved Spanish. Hebrew was a

liturgical language: it is as if one were to say that Catholics speak Latin.

Only recently, based on ancient Hebrew, was the language now spoken (only) in

Israel created.

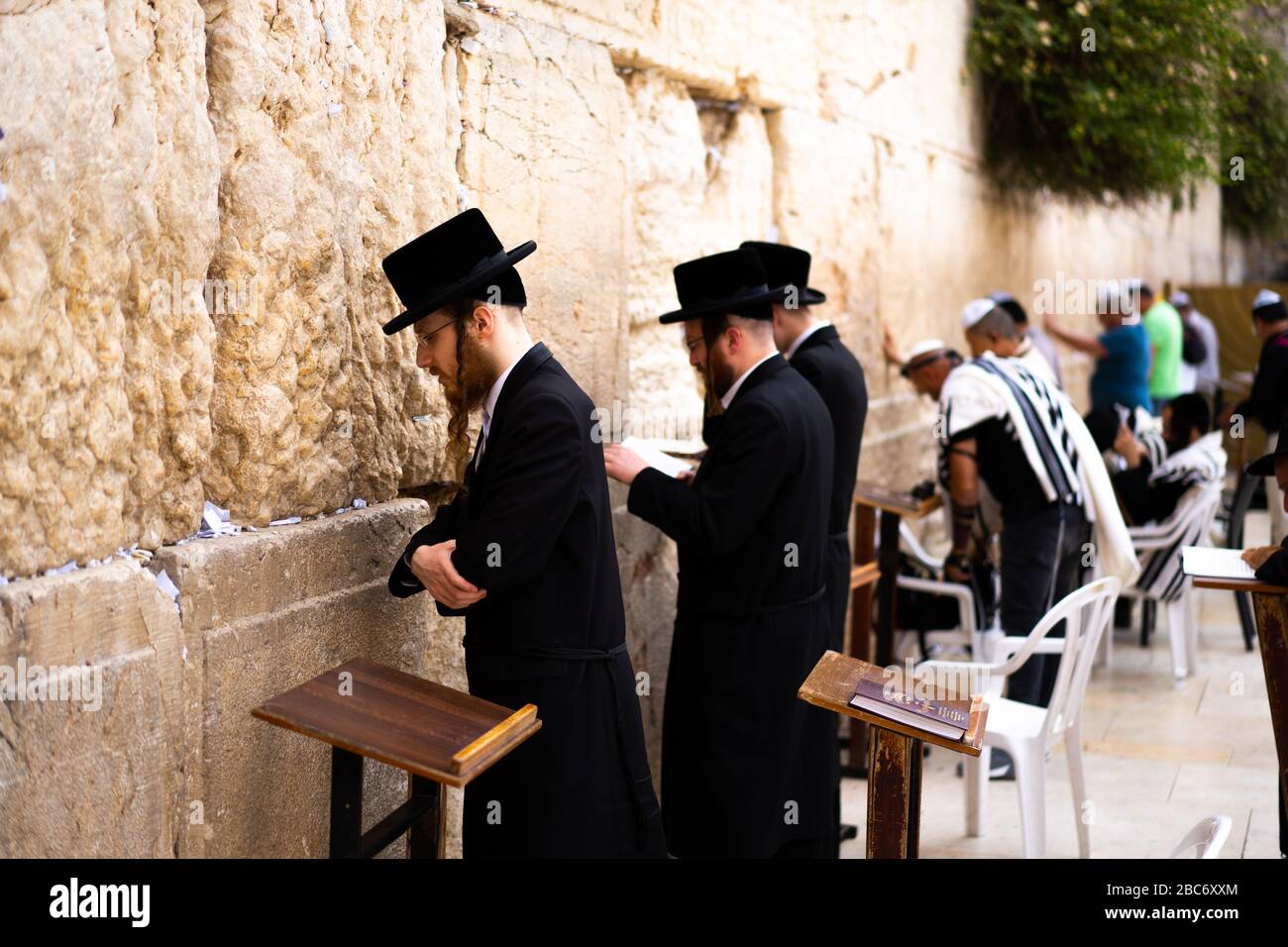

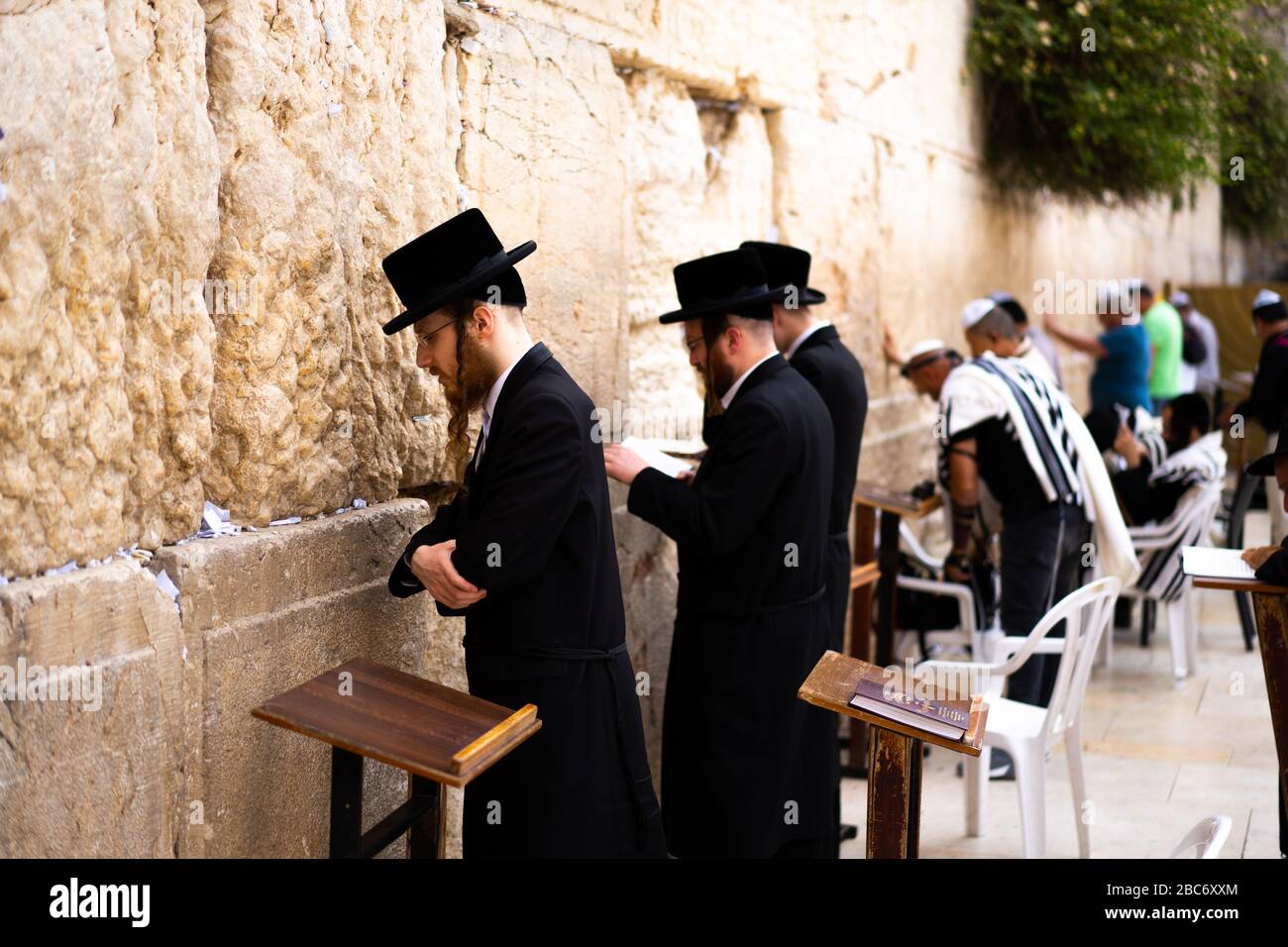

Besides the fact that most Jews are not

believers, even believers hold very different beliefs: even on basic issues such

as the immortality of the soul, opinions differ. One cannot speak of a single

religion.

In reality, therefore, no Jewish identity exists except that born of fear of

persecution and extermination.

The State of Israel itself was founded precisely to prevent Jews, in a world

where religion no longer defined a people, from being absorbed by the

populations among whom they lived.

Israel is a collection of diverse cultures, somewhat like the U.S., because its

people come from different countries whose cultures they share. A European or

Arab Jew does not differ from a European or an Arab.

On the other hand, no people shares a uniform culture; we Italians ourselves

differ greatly in opinions and ways of life.

It is true, however, that majority and minority mentalities exist, but in all

peoples everything and its opposite can be found.

Many, however, note that those who were racist

were in fact the Jews themselves, who consider themselves the people chosen by

God — a particular feature of the Jewish religion of the Old Testament, compared

with the universalism of the great religions. Certainly, it is a problem.

But this must be placed in historical context. In the past, religious wars were

common. One need only think, within Europe, of the persecution of Christians,

the terrible struggles among Christians over Christological issues, the medieval

heresies, and the most terrible of all: the struggle between Catholics and

Protestants. The same in the Islamic world.

Considering oneself preferred by God, even if not in the same way as Jews do, is

common: think of the destruction wrought by the conquistadors or even slavery in

America, which were also justified by the idea that at least the conquered

peoples would have access to eternal salvation instead of ending in eternal

damnation.

Judaism is not an exception.

Israel accepts all Jews and grants them

Israeli citizenship. This is not dependent on religion but on belonging to the

people of Israel, meaning being born of a Jewish mother, with some exceptions.

Strangely, however, one is not accepted if one practices another religion

(Christian, Muslim), since this is considered a rejection of one’s tradition —

something that would not apply if one were an atheist.

This seems to me a striking inconsistency.

Anti-Zionism consists in opposition to the State of Israel.

This opposition must be understood within the European cultural context. In the

early years all states, the USSR first among them, recognized and supported

Israel.

Later, however, Israel came to be seen as an expression of colonialism, a sort

of vanguard of capitalist, colonialist Westernism, and this led the political

left to strongly oppose it. Reinforcing this view was the fact that the USSR was

allied with the Arabs and America strongly supported Israel.

Subsequently the idea of Israel as a vanguard of capitalism faded along with

communist and far-left ideology, and it now survives only in some marginal

circles. Yet a general aversion to Israel has nonetheless persisted within the

democratic left as well.

What characterizes today’s radical Islamic world, however, is still the idea of

Israel as a vanguard of the West, of unbelievers against believers, and

therefore the conflict is not merely about reclaiming a small strip of

Palestinian territory, but a metaphysical struggle between believers and

unbelievers, between good and evil: and it is this that makes the Palestinian

question extraordinarily difficult to resolve.

It is also now assumed that all Jews support Israel.

But in any large community there is always everything and its opposite. For

example, among religious Jews — indeed, ultra-Orthodox Jews — there are also

those who oppose Israel: the Naturei Karta (“Guardians of the City”) consider

Israel blasphemous, side with the Palestinians, and at one point even took part

in Arafat’s council. But this certainly does not mean that Jews as a whole

oppose Israel.

As for current Israeli policy in the Gaza war and especially in the de facto

occupation of the West Bank, opposition from a portion — perhaps even a majority

— of Israelis appears significant.

Nor should the opposition to the Gaza war be confused (as Palestinians often do)

with opposition to Israel itself: these are distinct matters.

It is true, however, that in Israel a minority but growing ultra-Orthodox

component is emerging — what we might call the “messianic right” — divided into

three currents: Sephardic, Ashkenazi, and Mizrahi. Some believe Israel is

becoming a Middle Eastern country, in practice not very different from Hamas.

I do not know; the future will tell.