I feel extremely fortunate to have been born in a free and democratic Western country. Without a doubt, I believe in the importance of rights and liberties, and I think that democracy, despite its many flaws, is still the best political system—not necessarily the best possible, but the best one we've seen so far.

This is all true, but I also realize that these principles were instilled in me by the culture I was born into, educated in, and have lived in my whole life.

However, I see that not all of humanity shares my convictions. In fact, the majority of people not only don’t live in a democracy, but they often don’t even desire one.

Democracy doesn't work for all people, and it depends on a complex set of factors.

I'd say that democracy seems to work where there's a good level of culture, civility, and, above all, well-being.

You can't claim that democracy is an absolute good and everything else is evil; it depends on many factors.

Above all, I've noticed that democracy is only possible when it is accepted by the vast majority of the population. This belief doesn't exist in most of the world, so democracy isn't possible there, nor can it be imposed.

In this century, there have been attempts to impose (export) democracy, as in Afghanistan and Iraq, but these experiments have sadly failed because they weren't accepted by the majority of those people.

The question I ask myself is: Why don't these beliefs, which seem so obvious to us in the West, spread throughout the world and become universal?

Of course, some would say it's a matter of culture, mentality, and civilization.

That's all true, but in my opinion, the essential reason is different: political systems are judged based on the well-being—or lack thereof—that they produce.

We also have to acknowledge that each of us is much more interested in finding a good job, a good spouse, and a future for our children than we are in freedom of thought and free elections.

What truly matters is well-being in a broad sense, not just economic prosperity but also security and social provisions (pensions, healthcare, subsidies, etc.).

Therefore, we have to recognize that well-being matters more than democracy; that democracy also has many flaws; and that, deep down, the people who truly appreciate freedom are only a minority. Voter turnout, in fact, seems to be decreasing more and more, showing a decline in interest in politics and voting.

People judge a political system by the well-being it produces.

Democracy succeeds to the extent that it brings about—or is believed to bring about—well-being.

In China, well-being was brought about by a dictatorship. After visiting China, I saw incredible progress: in just a few decades, it went from a vast expanse of shantytowns to a forest of skyscrapers. It seems impossible to deny the progress of the Chinese people in recent decades.

And yet, there is no democracy in China, and the idea that progress would automatically lead to democracy has proven to be completely wrong.

I can't say whether democracy is the cause or the effect of our well-being. Are Western nations more prosperous because they are democratic, or are they democratic because they are more prosperous?

If we look at the past century, we must realize that democracy triumphed over fascism and communism in the West because it brought about well-being.

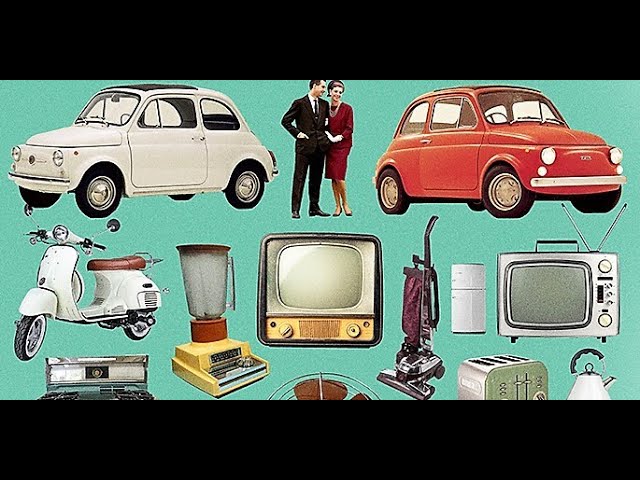

In Italy, democracy took hold because it led to the economic miracle.

Fascism collapsed not because people desired freedom, but because it led to the unprecedented disasters of war.

The end of communism was sealed by its failure to achieve the same levels of well-being as Western societies.

And we can continue through history:

The French Revolution was not supported by the French for the sake of liberty (which, incidentally, they didn't even get), but because it abolished feudalism, giving land to the peasants who had always wanted it, thereby raising their standard of living.

Similarly, the southern "cafoni" (a derogatory term for poor, uneducated peasants) joined the Army of the Holy Faith and overthrew the Parthenopean Republic because they realized it wasn't bringing improvements to their conditions, but only benefiting the rich.

Likewise, after Italian unification, there was hostility from the poor masses of peasants ("cafoni"), which led to brigandage, because the new state of affairs did not improve their miserable conditions but was a boon for the bourgeoisie. After all, how could a poor, illiterate peasant participate in freedom and politics? He didn't even have the right to vote, much less the possibility of being elected. Democracy and freedom were the affirmation of the interests of the bourgeoisie, who enthusiastically embraced them.