Origin

The Iranian political system is commonly thought of as an expression of a Shiite theocratic tradition. In reality, this isn't the case; it's a personal creation of Khomeini, and one, I would say, that contradicts the traditional Shiite conception of politics.

Various currents participated in the revolution against the Shah, including those inspired by socialism and Western secularism. Khomeini gained almost unanimous consensus because he was considered the heir of the recently deceased Ayatollah Ali Shariati, who held views very close to the Western left of the time. Shariati, a man of vast culture, both Islamic and Western, studied in Paris where he encountered the most vibrant post-war left-wing movements. He translated classics of left-wing thought like Sartre and even Che Guevara into Persian. He was captivated by the revolutionary and utopian ideology of the Western left with its ideals of social justice, a non-alienating society, without exploiters and exploited, which were then interpreted through a Shiite religious lens.

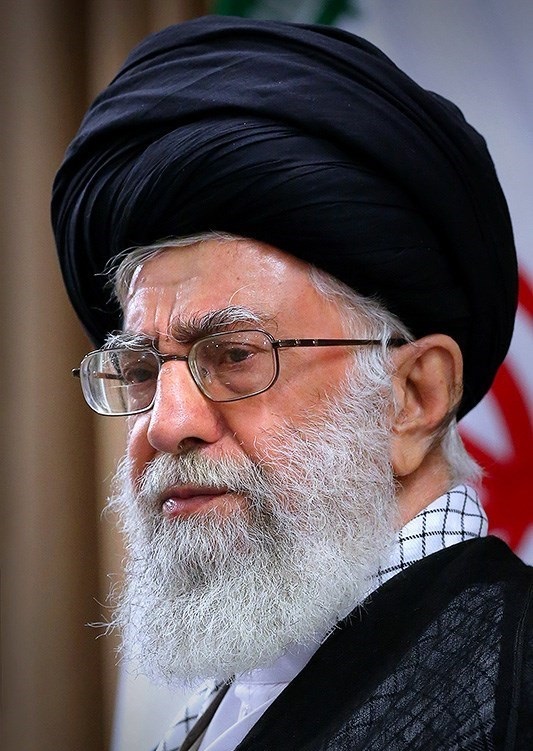

This explains how, in its early period, the Iranian Revolution was seen in both Europe and Iran as a left-wing revolution, albeit with an Islamic character, while it subsequently took the very different path of Khomeini. He quickly managed to marginalize all other components, concentrating all power in his charismatic figure and then developing an original constitution that is still in force today. When he came into conflict with President Bani Sadr, the latter, despite having been elected almost unanimously, had to flee within days, barely saving his life. Currently, Iran's President Pezeshkian, who would have more or less the same powers as Trump, appears to be completely ignored in practice, almost unknown to global public opinion, which instead only hears about Khamenei.

Structure

From a formal standpoint regarding political bodies, the Iranian constitution is similar to many other modern ones: the president of the republic is elected by direct universal suffrage, appoints ministers, and his power is counterbalanced by a parliament also elected by universal suffrage with a single-member system.

But superimposed on this system is an element that profoundly changes everything: the "Velayat-e faqih" (Guardianship of the Jurist), which is a religious authority that controls the conformity of the political bodies' actions with Islamic laws.

The Velayat-e faqih is actually made up of a Rahbar (master jurist), whom we call the Supreme Leader, assisted by twelve experts. This body would correspond to the Constitutional Courts existing under various names in modern states, but in fact, it has assumed a function of absolute power, effectively marginalizing the president.

Indeed, it does not only judge the religious conformity (i.e., the constitutionality) of laws, without delving into the merits of political action. Instead, it primarily judges who can and cannot participate in elections based on greater or lesser religious reliability. It intervenes, above all, in all political decisions, determining what is Islamic and what is not: foreign policy, alliances, the nuclear program, and domestic policy.

It should be noted that in Islam, there is no clergy as understood in Catholicism, as an intermediary between God and man, and therefore no religious leader as a representative of God on earth (the Pope with the keys of St. Peter). Therefore, the Rahbar is not the religious leader of Iranian Shiites; strictly speaking, his power is not a theocracy. The constitutional system is actually ambiguous because the limits of power for religious and civil authorities, both constitutionally provided for, are not well defined.

Even the succession was actually established by Khomeini. By his designation, the "grand ayatollah" Montazeri had been chosen, but when Montazeri began to hold different positions from him, Khomeini had him removed from the succession and placed under house arrest. Immediately afterward, Khomeini indicated Khamenei, whose only merit was absolute loyalty to his line, and who was indeed elected a few months after his death and is still the Supreme Leader.

Shiite Political Doctrine

The Shiite faction arose from the dispute over the succession of the Prophet Muhammad. When Ali, the last caliph (successor) from the House of Muhammad (Ahl al-Bayt; the people of the house) was assassinated and power then passed to the Umayyads, one of Ali's sons, al-Husayn, tried to reclaim power but was killed with 72 followers in Karbala in 680 CE. The Ashura is celebrated in remembrance of this event.

Other descendants claiming succession followed, a total of twelve "imams" starting from Ali. The last of whom was Muhammad ibn al-Hasan, known as al-Mahdī (the awaited one) who is believed not to have died in 874 CE but only to have gone into occultation, to return to earth at the end of time to establish the kingdom of God.

Shiism (the faction) is not, however, reduced to a simple dynastic struggle, but an interesting doctrine was developed that in many ways resembles Saint Augustine's "Civitas Dei." They argue that after Muhammad, a truly "just" community according to the dictates of God's law (Sharia) is not possible on earth.

The death of al-Husayn is not simply an episode of a trivial dynastic struggle, but takes on a universal and metaphysical meaning: it is the demonstration that good cannot triumph on this earth, and al-Husayn, who prefers to die with his followers rather than surrender to evil, is the martyr (shahid) par excellence, the testimony to the wickedness of men that does not allow for a truly just society. Hence the doctrine of "occultation": only at the end of time will al-Husayn return to earth to establish the truly just society.

Thus, we have a pessimism similar to the Christian pessimism of Saint Augustine: evil exists in the world; it will always remain indissolubly intertwined with good until the end of time when the world will be redeemed by the return of al-Husayn (in Saint Augustine, by the return of Christ, who will separate good from evil). In this doctrinal framework, Ashura is not simply the re-enactment of a historical event that happened many centuries ago, but it is mourning for the evil that is in the world, now as then, and in each of us. The painful penance with flagellations and self-inflicted wounds is the expiation of evil, the penance. Similarly, on our Good Friday, we remember not only the Passion of Christ but the evil that is in the world that calls for penance. In medieval traditions that have survived in some places to this day (Cusano Mutri), there are flagellations similar to those of the Shiites: the penitent expiates the evil that is also in himself, in his own sins.

In this complex ideology, the state is necessary to repress the evil that is in man ("remedium carnis," as Saint Augustine said) but cannot establish a truly just society. From this, it follows that civil power must be distinct from religious power; only with the return of Imam al-Husayn will the two powers unite in a single person, beloved by God. Shiites, therefore, like Saint Augustine and even Luther, lean towards obedience to the state even if it is, by its nature, imperfect.

Khomeini, however, superimposed a religious authority on the political power, which assumes a modern elective democratic guise, and this authority is supposed to judge whether its actions conform to God's supreme law. But in this way, political power is actually guaranteed by a religious authority and therefore could only act for the good, which Shiite doctrine properly does not admit. Inevitably, the evil that is inherent in politics by its nature, as in all society, would be transferred to the authority of the interpreters of religious doctrine.

In simple terms, if there is a religious authority that evaluates and guarantees the adherence of government acts to religious laws, then Iranian society should be a society where God's justice reigns. But this is not possible according to the Shiite conception of society, and on the other hand, no one can think that Iran is in fact a perfect society. Yet, the evil cannot be attributed to divine laws and their interpreters. Khomeini's conception is, therefore, in contrast with the traditional Shiite view.

Conclusion

In reality, Khomeini's Islamic revolution has largely failed. The theocracy has been maintained in the country for 45 years but has not spread throughout the Islamic world. In fact, the conflict has intensified, becoming open warfare with the vast majority of Sunni Islam. The ideal of theocratic governments is now pursued only by extremist and fanatical Sunni currents who, moreover, consider Shiites impious and enemies (the caliphate). For 45 years, Iran has mobilized religious consciences and strong national sentiment against an alleged international conspiracy of the entire world against the Khomeinist Revolution, with America as the "Great Satan" mobilizing the "Little Satans" of the Islamic world against the Shiite revolution. But an Iranian who follows world news a little via the internet, not only Western but also Indian, Chinese, Russian, and even Arab media like Al Jazeera, finds no enemy will in the world at all.

For the Ayatollahs, the whole world conspires against the Khomeinist revolution because the whole world fears it, because it is good against evil, light against darkness, truth against lies. But knowledge of Shiite Iran in the world is very modest. Often, journalists themselves show scarce information and, above all, scarce understanding. The world is not fighting with Iran; for the most part, it simply ignores it.

For the world, Iran's Islamic revolution is not the touchstone but merely incomprehensible fanaticism, an expression of backwardness, a danger to be eliminated if it acquires nuclear weapons. It is no coincidence that the followers of change in Iran are students, urban populations, and the bourgeois classes: they are the ones who have access to the internet and can see the rest of the world, while Khamenei's followers are mainly in the poorer, rural areas.

Indeed, in the current tragic events in Palestine, Iran's actions have appeared completely isolated, in contrast with all other Sunni states that are now leaning towards an inevitable recognition of Israel, already present in the Abraham Accords. October 7th was Hamas's desperate attempt to prevent them, which has succeeded for the moment, but at the cost of Gaza's extreme ruin.